Since January of 2000 I’ve traveled to Sierra Leone on six or seven occasions. Whereas my first few visits were for the purpose of researching a novel, my recent travels have been to assist friends in establishing businesses, a medical clinic for a birthing room, and schools for providing school fees for several high school students. The experience has been both rewarding and frustrating.

What is frustrating is that, despite the efforts of so many, the living conditions of average Sierra Leoneans never seem to improve. My Sierra Leonean friends cannot quote statistics from the World Bank (note 1) but they can all tell you about the cost of a bag of rice. I’ve met many who buy their rice, not by the bag, but by the cup.

Why?

My travels within the country and my time within the village of Sumbuya have given me the opportunity to observe both the Sierra Leonean government and foreign non-government organizations (NGOs) in action. Let me start by saying I’ve never met an aid worker who wasn’t completely committed to improving conditions for local people. With all the singing and dancing by hundreds of grateful villagers, it is hard not to think you’re doing the right thing.  I’m not so sure, however, that the country isn’t suffering unintended consequences for all of the good intentions.

I’m not so sure, however, that the country isn’t suffering unintended consequences for all of the good intentions.

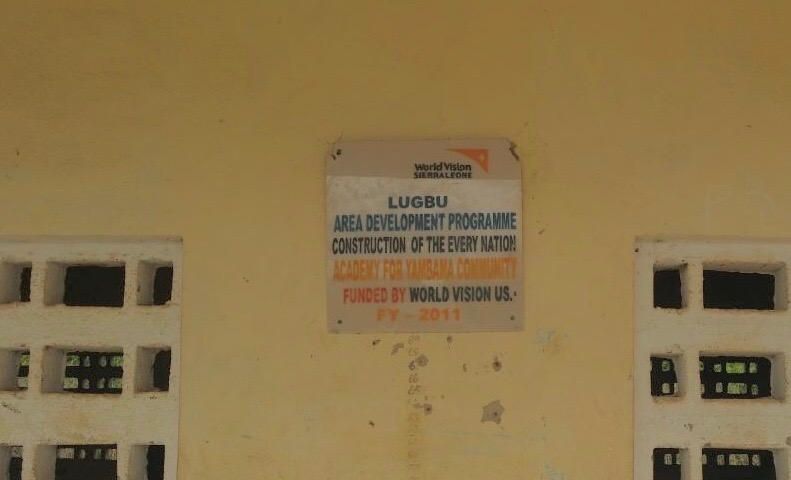

Sierra Leone is littered with rusting signs from aid programs that have funded schools, provided lunch programs for kids, or provided programs for ’empowering women’. I’ve stood in the classrooms of many of these schools–schools with blackboards with no chalk, staffed by under qualified teachers who use rote learning because that is how they were taught, ‘teaching’ pupils who cannot afford to buy text books even if available.

It is not uncommon to find grade-one classes with close to one hundred pupils and one teacher.  I’ve met many teachers who have submitted their qualifications four years previously but never been paid because the Education Ministry is too unmotivated to certify their qualifications. When asked why they teach when they are often unpaid, the teachers often tell me “I hope and I pray–what else can I do?”

I’ve met many teachers who have submitted their qualifications four years previously but never been paid because the Education Ministry is too unmotivated to certify their qualifications. When asked why they teach when they are often unpaid, the teachers often tell me “I hope and I pray–what else can I do?”

The irony is that large aid programmes assume the status quo as a given. They are here for the long term and give no indication they plan on leaving any time soon. In the villages I’ve visited it is not the Ministry of Education that has partnered with me to rebuild a school–it is the mega NGO, World Vision. In fact, World Vision is such a large player the local people refer to the local director as the ‘town manager’. Unapologetically, World Vision has taken the responsibility of government. The disincentive for the federal government to behave responsibly is enormous–why should they provide funds or leadership when a foreign donor organization is more than willing to?

has taken the responsibility of government. The disincentive for the federal government to behave responsibly is enormous–why should they provide funds or leadership when a foreign donor organization is more than willing to?

During my return to Lugbu Chiefdom this spring I experienced this firsthand. We were in a welcome ceremony in a local village where our family had sponsored a number of girls for school fees and some local teachers for ‘distance education’. The headmaster of one of the schools thanked us effusively. And then this: “And now on behalf of our schools we ask that you redouble your efforts. Please, we need a new well for fresh water, and a room for teachers, a new roof on the senior school, and our teachers have not been paid, so salaries for…” I cannot remember the rest of the requests but one thing was clear–the community expected nothing from government and we, the foreign donors, were the bird in hand…

The current generation of Sierra Leoneans view aid organizations as caretakers and caregivers–in contrast, government is viewed as corrupt and incompetent. When I ask children what they would like to do when they grow up they invariably say they would like to be either a doctor or work for an NGO.

In my view, Sierra Leone does not need another program to provide ‘micro-loans’ to assist women to become petty traders. Why? Because these programs set the bar too low. I’ve never met a petty trader who wasn’t living hand to mouth. Giving a loan to someone to become a petty trader may keep them from starving but it also keeps them poor. Micro-loans are a brilliant idea, but provide loans to entrepeneurs who actually employ people. The money from donors is a scarce commodity–give it to people who are most likely to make a difference not just for themselves, but for others.

Young Africans are entrepeneurial and many wish to become involved in business, however the barriers and disincentives to doing so are staggering.

One of the barriers, in my view, is the effect aid has had on the expectations of young people. I once had a long chat with a young man who was running for parliament. When I asked him how he thought his country would ever get ahead he said ‘more needs to be done to get foreign donors’. And when I asked him about taxation he said the country needs to put higher tariffs on imported goods to raise money…this in a country where the people cannot afford foreign goods as it is.

Dambiso Moyo, is an African economist and author of ‘Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa‘. She states that there are more African’s living in poverty today than there were in the 70’s–the period in which the ‘aid-culture’ of foreign donors providing billions of dollars of aid to African countries has been predominant. Moyo believes aid has contributed to market distortion and systemic dependency on aid which serves as a disincentive to mechanisms that would lead to growth.

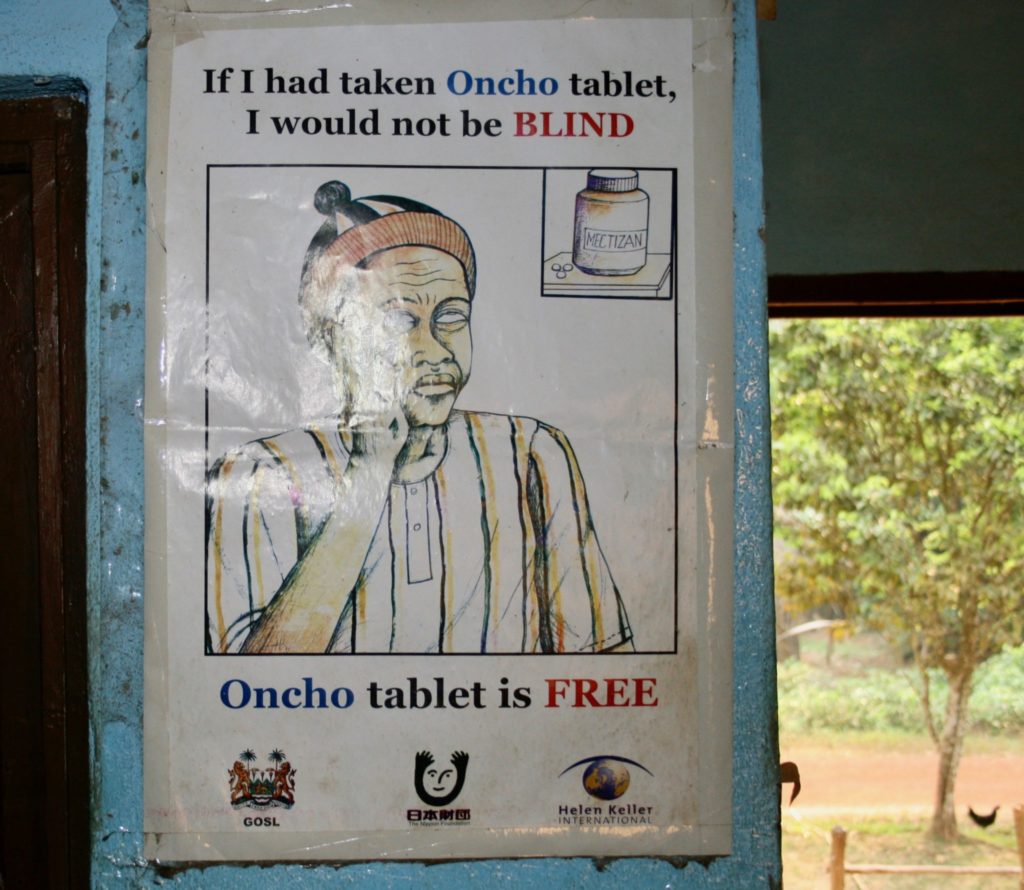

What does she mean by market distortion? Imagine the disincentive to a young entrepreneur wishing to start a business making mosquito nets when well-meaning NGOs provide them for free. Or NGOs paying night watchmen more than the government pays local teachers (or virtually anyone else who is locally employed). I’ve witnessed both examples of market distortion attributable to NGOs.

I will not repeat Moyo’s evidence here but I invite readers to consider watching any of the numerous youtube videos (see note 2) of Moyo’s speeches given around the world. She has been subjected to significant criticism, not the least of which coming from Bill Gates. I believe Gates wrongly suggests this is just a question of values–to him giving aid is simply the right and compassionate thing to do: “If you look objectively at what Aid has been able to do, you’d never accuse it of creating dependency.” (note 3)

I agree with Gates that the use of vaccines, medical and emergency food programmes has saved thousands of lives and are worthy of foreign aid. To cite one example, Medicins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders) has saved thousands of lives working in high risk conflict zones around the world. I personally have provided financial aid to educational programs, financial and logistical aid to families developing businesses to sell solar lights, and personal aid to a number of families. I remain, however, an aid critic and I disagree with Gates suggestion that aid critics like Moyo and myself have questionable values. Moreover, for Gates to suggest that aid has not created systemic dependency among African governments is ludicrous.

To take Sierra Leone as just one example, if government was not dependent on mega aid programmes these programmes simply would not be operating in some capacity in every province in the country.

I agree with Moyos’ suggestion that a better model for NGOs would be to make programs ‘short, sharp and finite rather than open-ended’. Go in with a specific goal, achieve it and move on. By all means focus on assisting African startup companies to make their own mosquito nets, solar lights, clothing and other consumer goods while employing people at the same time–and without having to contend with market distortion attributable to well-intended NGOs.

Note 1: World Bank figures put inflation in 2016 at close to 17.5% while the Leone devalued by almost 29%.

Note 2: Moyo on aid

Note 3: Bill Gates on Dambiso Moyo and his views on aid.

Leave a Comment